Art and Technology

One of the reasons I was most excited about choosing Brown was our independent concentration program. Every student at Brown needs to complete a concentration (our 'majors') to graduate, but if a student doesn't like any existing options, they can propose their own. The process is no joke; proposals require faculty sponsorship, run 15-20 pages long, and some people rewrite and resubmit their applications 5+ times before being approved.

I knew going into Brown that I wanted to study computer science, but also to get a real grounding in the liberal arts. I love to read and write, so I'd initially declared in English. However, over time, I found that all of my humanities and media interests drifted towards technology (multimedia art, literature about modernization, industrial design), and all of my technical interests drifted towards media (graphics, computer vision, hypertext). The humanities-y classes I took also went well beyond the English department: courses at RISD, in architecture and art history, even in computer science.

I'd always explored the possibility of doing an IC, meeting a few of the IC advisors my freshman fall, but didn't end up submitting until the last possible deadline. My first title was "Modernism," which quickly evolved into Art and Technology.

As I wrote in my proposal (which you can read here): "Art and Technology is an interdisciplinary study of how cultural production and technological development interact."

Here's every class I took for the concentration:

- HIAA 0850 (Modern Architecture)

- RISD 0750B: History of Industrial Design

- CSCI 1951V: Hypertext Hypermedia: The Web Was Not The Beginning and the Web Is Not the End

- ENGL 1511P: Realism, Modernism, Postmodernism

- HIAA 0820: Art and Technology

- ENGL 1580: (Independent Study) Modernism and the Corporation

- HISP 0750X: Environmental Arts: Film, Literature, and Photography

- APMA 1875: Form and Formalism

- ENGL 1751D: Hollywood and American Modernism from FDR to JFK

- Capstone/Independent Study

The Work

Some of my favorite projects I did for the concentration were:

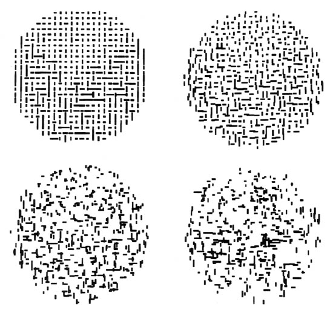

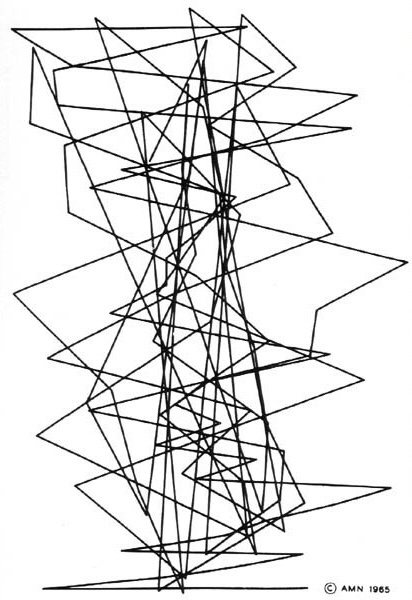

Bell Labs and Early Computer-Generated Film

I'm particularly interested in works where artists experiment with the affordances of new technologies. In the case of computer graphics, some of the most interesting works come from ties between engineers and artists, like Pixillation (1970) by Lillian Schwartz, a visual artist, and Ken Knowlton, a communications engineer. The two worked with new mainframes like the IBM 7094, with breakthroughs in computer graphics allowing for the Stromberg-Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter. The final film contrasts computer-generated patterns (made with the BEFLIX animation language) with hand-painted frames and film of natural crystal formations.

One of the coolest parts of this history for me was that Andy, one of the professors I TAed for worked with many of these pioneers; I'd often text him midway through writing to ask about their work.

This history is most interesting to me because of the ways in which it exemplified common dynamics in artist-engineer collaborations. For example, Ken Knowlton's early graphics language had to be changed for artistic use:

"[BEFLIX] was not originally designed…for presentation of artistic material. That is, working with Lillian, Ken realized that his language was…scientifically oriented…and that…it is necessary to develop special facilities for the artists."

- quoted by Lillian Schwartz in The Computer Artist's Handbook

Artists typically did not have the technical skills to work with computers directly, so their artistic visions were modulated through the engineers they worked with. As such, the roles of artist and engineer often blurred.

In the early work of Kenneth Knowlton and Michael Harmon, for instance, a coin was flipped to see who would be the engineer and who would be the artist— just one instance of how irrelevant these labels could be. And yet these labels cannot simply be ignored because they often had significant real-world implications—for how this work was made, where it was exhibited and encountered, and the discursive models through which it was discussed and conceptualized.

- Zabet Patterson, Peripheral Vision: Bell Labs, the S-C 4020, and the Origins of Computer Art

Computer art works, also, historically have fallen between the cracks in terms of where they are received and understood:

Some presented at computer conferences and SIGGRAPH (the ACM Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics, founded in 1969). Others circulated in experimental film networks, museums, galleries, and university MFA programs. Far from a cohesive school of practitioners, some of the artists discussed in this essay may have crossed paths during these formative years, but they all pursued their own routes there-after, as researchers, educators, filmmakers, and visual effects artists. "Starting afresh each time," to recall Whitney's words.

- Britt Salvesen, Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982

These collaborative dynamics are also laden with asymmetry, often because of power relationships dictated by both disciplines:

"The artists wanted respect; they wanted their world recognized as professionally rigorous; they wanted their contribution to stand equally alongside that of scientists, engineers, and businessmen…humiliation, however muted or disguised, is a measure of their own fascination with, and desire to bathe in, the lustrous aura emanating from high-status, high-powered Cold War elites".

- John Beck and Ryan Bishop, Technocrats of the Imagination: Art, Technology, and the Military-Industrial Avant-Garde

Capstone: IBM, Olivetti, and the Informational Turn

For my capstone, I wrote a paper and gave a presentation about ways information theory inflected the early design philosophies of IBM and Olivetti. You can watch my presentation at the IC "Theories in Action" symposium here:

You can read my final paper here, or my Goodreads reviews/research notes for everything I read below, mostly design history and early history of computing stuff:

- John Beck and Ryan Bishop, Technocrats of the Imagination: Art, Technology, and the Military-Industrial Avant-Garde (2020)

- Paul Edwards, The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America (1996)

- Pamela Lee, Think Tank Aesthetics: Midcentury Modernism, the Cold War, and the Neoliberal Present (2020)

- James Gleick, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood (2011)

- Reinhold Martin, The Organizational Complex: Architecture, Media, and Corporate Space (2003)

- John Harwood, The Interface: IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design, 1945-1976 (2011)

- Lindsay Caplan, Arte Programmata: Freedom, Control, and the Computer in 1960s Italy (2022) by Lindsay Caplan

- Claude Shannon, The Mathematical Theory of Communication (1949)

- Justus Nieland Happiness by Design: Modernism and Media in the Eames Era (2020)

Institutionalizing the ‘Great Man’: Collectivity and Individual Ambition in Modernism

I wrote this paper for one of my advisors' classes, "Hollywood And American Modernism, from FDR to JFK." I focused largely on the tension between individuals and collectives, whether they be within a large organization or situating themselves within a canon. To do this, I compared five different works of the time: T.S. Eliot's "Tradition and the Individual Talent," Robert Wise's Executive Suite (1954), Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead, William H. Whyte's The Organization Man, and Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

It's a pretty wacky paper—I might be the first Brown undergrad ever to write about Ayn Rand—but I had a lot of fun with it, and used the exercise to work through some of my own lingering questions about this stuff. You can read my paper here.

I should also note: "Executive Suite" became one of my favorite films ever. Introduced to me as “the liberal fantasy of capitalism” or “like “12 Angry Men” for business. Executive Suite centers on the death of Avery Bullard, President of the Treadway Corporation, a business known for manufacturing furniture. He has not named a successor; there are five vice presidents, vying for the top spot. In the course of one weekend, the board will choose a successor and Shaw, a kniving finance VP seems like he will take the top spot. In the end there is an incredible scene where Don Walling, the head of research and development, makes his case, successfully:

Would you be satisfied to measure your life's work by how much you raised the dividend? Would you regard your life a success, just because you managed to get the dividend to three dollars, or four dollars, or five, or six, or seven. Would that be enough, is that what you want on your tombstone when you die?

It’s a really beautiful ode to quality, excellence, and taking pride in one’s work, something I keep coming back to. You can watch the outstanding and rousing ending monologue here:

Plan for a Providence City Center

In my freshman fall, I used OpenSCAD to recreate an unbuilt mel of Raymond Hood's "Plan for a Providence City Center." I wrote a lot more about it for my portfolio, which you can read here.

The People

Two professors were most impactful in helping me shape this, Prof. Deak Nabers in English and Prof. Lindsay Caplan in Art History. I'm also deeply indebted to Peggy Chang, who runs the IC program, who helped me shape my proposal and navigate the process: